This is the eighth article in the Making Sense of C series. In this article, we're going to discuss how the computer works with memory in order to figure out how to keep track of where a list starts and how we can use memory addresses to make a list. Once we can make a list, we can make a string easily. Plus, a list is just a good tool to have.

Since we've done a lot up to this point, I'm just going to use a list to make it easier to read. So far, we've

// for single line comments and /*

and */ for multiline comments,

+-*/% for arithmetic,

[type] [variable] = [expression] which will allow us to store

values for later use,

char, short, int, and long long) and

the floating point types (float and double),

char type and invented the

NULL character, which indicates that we're ending a string,

char.

Although we can represent individual characters, we need to string them together

so that we can represent actual text.

We decided to solve the problem by putting characters in a list, specifying the

beginning of the list, then telling the computer to keep reading the list until

it reaches a special character we call the NULL character, which we represent

with a '\0'.

There are a lot of terms that we know them when we see them, but we have a hard time defining them in a concrete, meaningful way. To make sure we have a clear goal, we're going to come up with a formal definition of a list.

In computer science, a list has a few properties:

Since we neither have infinite RAM nor time, the last property is satisfied, but we're going to have to implement the other properties. If we know the first element and we know how to access the next element in the sequence, we will have an implementation of a list.

Locating an element of a list is actually related to another problem that we've

put off, namely how does something like int a = 84; get converted into

something the machine can read?

Up to this point, we've been working almost entirely from what we, as

programmers, will see.

We deal with variables and arithmetic and types, but the computer just sees ones

and zeros.

Since computers have no concept of a variable, how can we actually implement a

variable?

Remember that a variable stores a value for later use, and the only way we can

store data for later use is by using memory.

When your computer sees something like int a = 84;, it will first tell the

operating system to give it four bytes (ints need four bytes for

representation) somewhere in memory, then it will store 84 in a register, then

it will store the value in the register into the four bytes allocated for a.

When the computer later sees a statement like a += 17;, it will load the value

stored in a from memory into a register, add 17 to the value in the

register, then write the value in the register back to wherever a was

stored.

When I describe what your compiler does at this part of the series, I'm assuming that it's not optimizing everything and converting exactly what you have written in your code into machine code. For example, your compiler will not allocate memory for a variable if it doesn't need to. Instead, it could store it in a register, which increases program speed since it doesn't need to copy anything from memory into its registers.

In assembly (the human version of machine code), this process would look something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | ; Assembly generally uses ';' for comments like how C uses // ; This part will first load 84 into register 8 (It doesn't matter ; which register I pick, so I just picked one), then store the value ; in register 8 into the memory for a, which is 28($29). ; I know 28($29) is some weird syntax, but it will make more sense ; once we finish the article. ; It means that you should store the value in register 8 into the memory ; location with an address of 28 + whatever memory address is stored in ; register 29. li $8, 84 sw $8, 28($29) ; Other stuff. ; This part will then load the value for a into register 14 (Once ; again, I just picked a valid register at random.), then add 17 to ; the value in register 14, then store it back into the memory for a. lw $14, 28($29) addiu $14, $14, 17 sw $14, 28($29) |

In short, the computer uses memory addresses to identify which bits of memory to change.

If you remember back in the variables and

basic arithmetic article in this series, I defined rvalues as expressions

that cannot appear on the left of an assignment operator and lvalues as

expressions that can appear on the left side of an assignment operator,

which is an accurate definition, but since I'm bringing up memory addresses, I

want to mention that the technical definition of an lvalue is a value with a

memory address and an rvalue is a value without a memory address.

For example, variables have memory addresses, but a constant like 5 does not.

This alternative definition should make sense because I can't store a value

unless I have memory in which to store it.

When we started this article, we had two problems to solve: how to specify the beginning of a list and how to implement a list. Memory addresses will let us solve both of our problems. Specifying the beginning of a list is trivial, since we can just give the computer the memory address of the first character, but how can we specify the next character in the list? We can either somehow group together every character with the memory address of the next character in what is known as a linked list or we can come up with a way that the computer can figure out what character to access next based on the current character and its memory address.

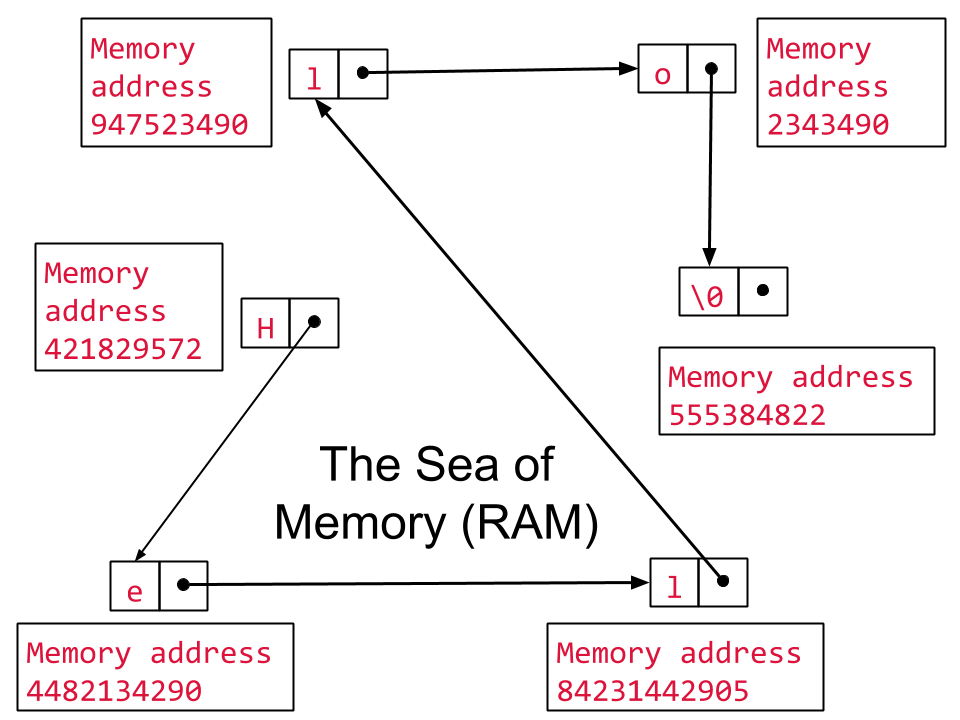

Here's what that would look like:

Each arrow represents a memory address that points to the next character in the string that we have to store with the current character. The memory addresses are basically random numbers I picked because the memory addresses you will get from the computer will seem to be random to you. Notice that none of them are anywhere near each other in memory, and they don't have to be either. Furthermore, to find the fifth element, you have to start with the first element, then go through each element until you get to the end.

Because linked lists require five or nine times as much memory to store a character and the memory address, they have no sense of cache locality, and you have to go through the entire list to see the last element, we're going to use an algorithm to find the next character.

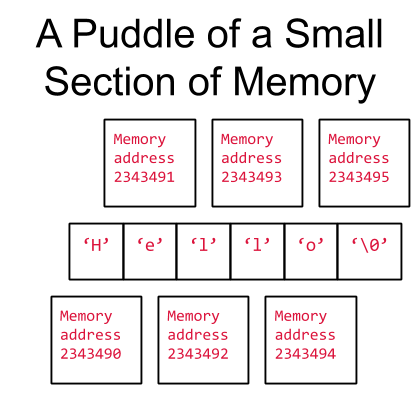

While there are probably many different algorithms we could implement to figure out the next character from the current character, the simplest algorithm is to put all the characters in a block of memory in order and tell the computer to access the character that comes next in the block of memory. As with the linked list, here's what that would look like:

Every single character is right next to the other character and to access the

string requires only the memory address of the first one, since we just have to

add one to the memory address of the current character to get the memory address

of the next character.

If we want to process strings, we can then find some way to loop through the

characters until we see the null character, \0.

In terms of speed, we can generally get around 64 characters into the cache at a time, meaning we only have to move something into the cache one sixty-fourth of the time.

We now have a few things to implement:

Since it's going to happen often, we should try to make accessing the memory

address of some variable something short so you don't have to type as much.

To get the memory address of a variable, we need to know what variable we're

accessing, so we're going to have something of the format •[variable],

where • is some character on the keyboard.

Well, we can't use any letters or numbers, and address sounds

like ampersand, so let's use &.

We've decided that &a will return the memory address of a.

Same as accessing the memory address of a variable, we want something of the

format •[variable] where • is some character on the keyboard.

Assembly used * to access values at memory addresses, so let's keep it.

We've decided that *[memory_address] will return the value at

[memory_address].

You can think of * as undoing &, meaning *(&a) is exactly

equivalent to a.

The act of getting the value stored at a memory address is known as dereferencing the variable.

Since memory addresses shouldn't be treated like any of our existing types and

we need to know what type the memory address represents, we need to come up with

some new types, which we'll call pointers because they point to locations

in memory.

Since we're already using * for dereferencing, let's use it in our types.

The syntax for a pointer variable is [type] * [variable_name];.

Like normal variables, we can assign them on the same line using the syntax

[type] * [variable_name] = [memory_address];.

A pointer to a [type] has the type [type] *, which is a distinct type from

[type] and you generally can't mix them.

int a = 48; // a is a normal variable int * b = &a; // b is a pointer to a, meaning it contains the // memory address of a float c = a * 48 / 2.0; // c is a normal variable float * d = &c; // d is a pointer to c, meaning it contains the // memory address of c

Remember that *(&a) is exactly equivalent to a.

Since b is &a, *b⇒*(&a)⇒a, which means *b =

17⇒a = 17.

In other words, dereferencing a pointer allows us to set or read the memory

it's pointing at.

In C, blocks of memory are known as arrays (or buffers in some

contexts).

There are actually two different ways to get a block of memory in C, but for

now, we're just going to get a block of memory in the simpler way (using the

stack) without really explaining it.

To get a block of memory, we need to tell the computer three things:

Let's keep the type and the name in the same spot as we usually do but add the

number of elements in the array somewhere in the declaration.

In C, the syntax to declare an array is type

variable_name[number_of_elements];.

I had to abandon my usual practice of putting the general name for things in

square brackets since arrays have square brackets in them.

Let's declare a bunch of arrays in C of different types so you get the idea:

int array_of_ints[14]; // Creates an array of fourteen ints float array_of_floats[50]; // Creates an array of fifty floats double array_of_doubles[64]; // Creates an array of 64 doubles char string[30]; // Creates an array of 30 chars

If you just declare a pointer variable, then you've only allocated the memory to store a memory address and not a list.

int * not_an_array; // Allocates four or eight bytes for a memory // address char * just_an_address; // Allocates four or eight bytes for a memory // address float * a_normal_variable; // Allocates four or eight bytes for a memory // address double * only_one_value; // Allocates four or eight bytes for a memory // address

We're almost there.

Remember that I said that we were going to use memory addresses to implement a list, but arrays don't look like they have anything to do with memory addresses besides the fact that we know arrays put a bunch of the same things next to each other in memory. What gives?

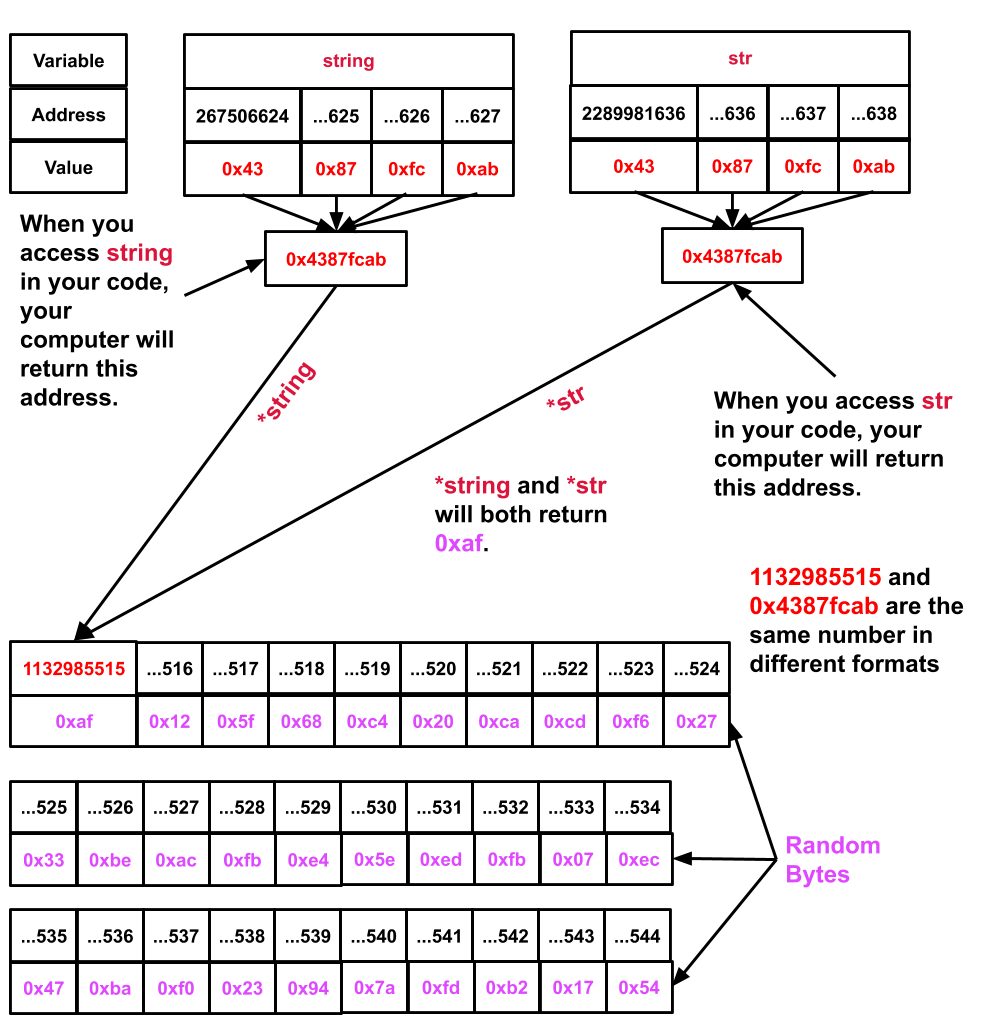

char string[30]; char * str = string;

When the compiler sees the preceding code, it will:

string.

Say the memory allocated in this step has address 267506624 (which will appear

random to you).

Currently, the data at 267506624 and the next three bytes contain random data.

chars (1 byte per char * 30

chars).

The values in the memory allocated in this step will be the text itself.

Say the first byte of memory allocated in this step has address 1132985515,

which I'll rewrite in hexadecimal as 0x4387fcab as every two characters after

the 0x (the 0x just means a hexadecimal number for people reading it) will

correspond to a byte.

string.

The memory at 267506624 now contains the byte

0x43, the memory at 267506625 now contains

the byte 0x87, the memory at 267506626 now

contains the byte 0xfc, and the memory at 267506627 now contains the byte 0xab.

Some computers will do it backwards where 267506627 will store the byte 0x43 and 267506624 will store 0xab.

It will not change your code unless you're sending data to another

computer, in which case you'll be able to use a library that converts it to

the proper format.

str.

Say the memory allocated in this step has address 2289981636.

Currently, the data at 2289981636 and the next three bytes contain random

data.

string into the memory

allocated for str.

Since str has the value 2289981636, the memory at 2289981636 now contains the byte 0x43, the memory at

2289981637 now contains the byte 0x87, the

memory at 2289981638 now contains the byte

0xfc, and the memory at 2289981639 now

contains the byte 0xab.

Here is what the memory will look like after these two processes have completed:

I want to emphasize that the thirty bytes of data allocated is not the same as the address of its first element. Your address written down on a piece of paper is not the same as your house and it's in a different place, but it will allow me to get to your house.

The inability to distinguish between the two of them is one of the biggest

obstacles in C.

The previous line of code is entirely valid because string is a char * that

points to the first character in the array of thirty characters.

In fact, if you wanted to right now, you could set the first character of the

string using

*string = 'H'; // OR *str = 'H';

Remember that both string and str contain the same memory address, so

dereferencing it gets the same exact memory.

That's all well and good, but how do we access the next character in the string?

*(string + 1) = 'e'; // OR *(str + 1) = 'e';

What about the next character?

*(string + 2) = 'l';

We could keep going, but we're wasting time typing everything out. It would be nice if we could just give it a list of characters on one line when we started so we didn't have to worry about it.

// This is actually two lines, but remember that C doesn't care about // whitespace or newlines. There's still only one semicolon, so it's one // statement. char string[30] = { 'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', ',', ' ', 'W', 'o', 'r', 'l', 'd', '!', '\0' }; int list_of_ints[20] = { 23, 52, 12, 5, 86, 24 }

Everything after the last element in the list will be set to zero (the null

character IS zero, which is why we denote it with '\0').

Typing out a bunch of ints isn't too bad, but typing out all these characters

with all the single quotes is just annoying.

Plus, what if I forget the '\0' character?

There should be a way to represent a string without having to type out the

single quotes, commas, and the null character, so let's make one.

char string[30] = "Hello, World!";

We chose double quotes since normal code is what the computer is thinking and

text is going to be how it communicates with us.

We also chose single quotes earlier for chars like 'A' because of how they

relate to strings.

For either an array of ints or a string, we would probably want the array to

be exactly large enough to store all the elements, so we shouldn't have to

specify the number of elements.

char string[] = "Hello, World!"; int list_of_ints[] = { 23, 52, 12, 5, 86, 24 };

The compiler will figure what number it needs to put in the square brackets for us.

You cannot, however, do

char string[];

because the compiler doesn't know how much memory you want to allocate for the string.

What if we want to change the array after initializing it?

string = "Hello, Other World!"; // Your compiler will print out "error: // Expected expression before '{' token" or // something like it. string = { 'T', 'e', 's', 't', '\0' }; // Same error list_of_ints = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}; // Same error

Once you've initialized an array, you can't reinitialize it later. I will show you why later in the series, but for now just know that you can't reinitizialize an array later. You can, however, change what a pointer points to like so

char string[30] = "Hello, World!"; char other_string[50] = "Hello, Other World!"; char * str = string; str = other_string;

You can also change individual elements of an array using

char string[30] = "Hello, World!"; *(string + 4) = '0'; // string is now "Hell0, World!" *(list_of_ints + 2) = 75; // list_of_ints is now { 23, 52, 75, 5, 86, 24 }

That syntax works, but it's way too verbose.

To make some new syntax, we'll need to know the name of the array and the

offset, so let's give it the syntax variable[offset].

string[12] = '?'; // string is now "Hell0, World?" list_of_ints[0] = 6; // list_of_ints is now { 6, 52, 75, 5, 86, 24 }

Remember that the first element of an array is zero because array[offset]

becomes *(array + offset) and array is a pointer to the first element of the

array, so array[0]⇒*(array + 0)⇒*array.

In this article, we

&),

*),

type * variable_name;,

type

variable_name[number_of_elements];,

char array using double quotes

("Hello!"),

variable_name[offset].

This article introduced a lot of new syntax, so feel free to read it over. Our file should now look like

// Initializing an array of characters (a.k.a., a string) char president_23[] = "funny valentine"; president_23[0] = 'F'; // president_23 is now "Funny valentine" president_23[6] = 'V'; // president_23 is now "Funny Valentine" other statement; // We've almost covered most of the statements we can // make. // We can make a list of numbers unsigned long long profits_per_state[] = { 15294, 3232, 10000, 5943, 57243 }; unsigned long long tristate_totals = totals[0] + totals[1] + totals[2]; double conversion_rate = 106.382830532840; unsigned long long tristate_totals_in_yen = conversion_rate * tristate_totals;

By allowing you to directly interact with memory, C introduces several

security vulnerabilities that mainly consist of accessing memory outside of a

buffer.

In other words,

float example[100]; example[1000] = example[-7]; // VALID C CODE

will compile and run. It might crash the program and exit safely or it could run another program with the ability to access and modify your secure data.

As a programmer, you must do everything in your power to keep your code safe. Obviously, if someone just gives out a password, there's nothing you can do, but if you have a security vulnerability that allows other users to read your passwords, that's on you.

As of right now, we neither have the capability to allow or prevent a malicious user from accessing memory outside of a buffer, so we'll save that for a later article.

We have a bit of a problem, though. For our program to work properly, we have to know how many elements will be in a list before we compile the code. If we're reading some text, for instance, and we want to make a list of all the unique words, we have no way of knowing all the unique words beforehand. We'll have to allocate a huge block of memory that's large enough to store all the unique words in every possible text, which would end up wasting massive amounts for any shorter text. What we want, therefore, is a way of getting a variable amount of memory so that we can get more memory when we need it and less memory when we don't.

We're going to neglect getting a variable amount of memory, since our first program to count the number of times a word the user specifies will not require it and because we need to introduce a few more concepts before we can understand why we can't just request a variable amount of memory using the method we introduced in this article.

For now, we're just going to assume that every word is less than 1024

characters, which could be exploited if someone gives us a "word" longer than

1024 characters (i.e., a string of alphabetic characters without a newline,

space, or any punctuation).

I'm also going to assume that you aren't going to try to break your computer, so

it's fine here, but you should make no assumptions about the input unless you

yourself generated the input completely independently from anything the user can

do, and even then, you should still be careful.

Anyway, if we're going to count the number of times a word shows up in some text, we're going to need some way to tell if two strings have the same characters, which means we're going to need some way to check a bunch of characters in a string and some way to add to the count if we find that the two words match.

In the next article, we're going to introduce Control Flow in C, which will be our first step in making our program do different things given different input.